had not died if Angie Martinez did not cry relentlessly on our radio dials (when she was still the king of Hot 97) the day of B.I.G’s funeral if the Daily News did not give the “King of NY” the front cover treatment if Brooklyn did not shut down for the funeral procession if Diddy had not danced in the white suit with Faith Evans and those kids―those beautiful kids―running the background if we still didn’t have stills of a crying Lil’ Kim being held up by Mary J. It’s hard to say now how a thirty-four year old me would respond to the album if it first dropped if B.I.G. The multiple backstories and innuendos on various tracks are a litany of Hip-Hop breadcrumbs: potential Tupac references in Long Kiss Goodnight, subliminal NaS disses on Kick in the Door, west coast affinity on Going Back to Cali, Biggie was spreading thought-starters across all twenty-four tracks. Fat Joe, on ESPN’s “Highly Questionable,” suggests Biggie was talking about Anthony Mason on I Got a Story to Tell. “I Got a Story to Tell” was one of ― if not the ― greatest Hip-Hop stories never told, due to the sheer genius of its lyricism, wit, and wordplay but the fanaticism involved in trying to find out which Knick player Biggie was referencing in the song?Īnthony Mason. Buck would also claim ― flat out ― B.I.G. Buckwild produced the now infamous I Got a Story to Tell. But, there would be one record that I would never forget, with the frame nailed to the wall and paint attaching itself to its history: The Notorious B.I.G.’s Life After Death album. The space was minimal, affording room for the records to breathe their breath over whomever hovered over them. Buckwild and I were there to talk business―music business―but all I could do while sitting on his all-white plush seating sofa was stare at the plaques. Going down the list of names of D.I.T.C reads like a discography of epic proportions. For those not in the know, Buckwild is the prolific producer of the famed Digging in the Crates crew (D.I.T.C.), home to Hip-Hop legends Big L, Fat Joe, Diamond D., Lord Finesse, Showbiz and AG.

#LIFE AFTER DEATH BIGGIE ZIP FULL#

On display with Life After Death was the full arsenal of what Biggie possessed: charisma, wittiness, a sharp and distinct flow and a powerful lyricism with remarkable story-telling.ĭ and I get off the train and walk a couple blocks and ring a doorbell to a private house, located somewhere in the Bronx.

#LIFE AFTER DEATH BIGGIE ZIP CRACK#

Biggie was giving us news, he was giving us the “Ten Crack Commandments,” he was giving us skits a la Prince Paul in the De La Soul days ― Jay Z offering up his thoughts on Mike Tyson and boxers pulling Pete Rose moves, R&B magic with a pre-peeing on underage girls Robert Kelly ― the full arsenal of artistic emcee prowess. Yes, you had to purchase CDs! But for Biggie, we took no shorts D went to Music Factory on the Fordham Rd., copped the cd, and came back to the crib, and we listened ― no different than families would do almost forty and fifty years prior, tuning into FDR or JFK on their radio stations. Our only source of music information and purchasing at the time was the bootleg man (if you don’t know, ask me) on Fordham Rd., or Music Factory, Circuit City, HMV, and Tower Records. This is before the days of LimeWire, Napster, and what would follow thereafter ― SoundCloud, iTunes, Spotify, Tidal and a bajillion other streaming music sites.

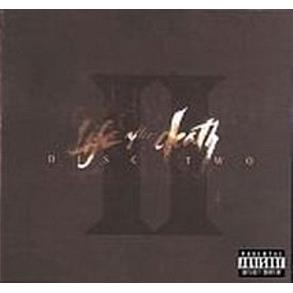

D and I sat in our mother’s two-bedroom in the Bronx, and I watched him unwrap the double-CD packaging (a feat in and of itself, seeing how Tupac was the only mainstream Hip-Hop artist to venture into the double-disc territory with “All Eyez on Me,” which was released a few months prior to Tupac’s unsolved murder), and listened―all the way through―with our added hood-side commentary (“yooo, rewind that back.lemme hear that again” and “He said what?!”) to what I still consider a masterpiece of modern art.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)